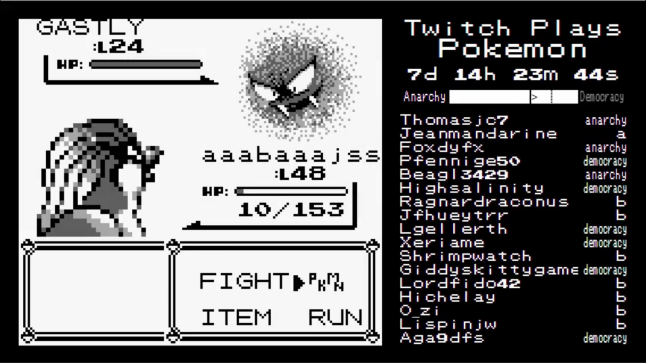

Twitchtv has become the home of many of the most avant-garde modes of play currently circulating in the digital space, from world first speed runs in the name of charity; to popular streaming sessions resulting in worldwide server shut downs and of course, the various international e-sporting events. The latest development to take place upon this platform is undoubtedly one of the most unique yet however. ‘Twitch Plays Pokemon’ (TPP) see’s the audience for the stream of a Pokemon Red (Nintendo, 1996) game directly control the actions of the player via chat commands that correspond to the options available in-game. Up, down, left, right, A, B, start, select – the original gameboy inputs – are the options available and whatever proves to be the most popular input from the viewers in the chat box results in that action taking place in the Pokemon game.

It’s an elegantly simple premise and one that has proven to be phenomenally popular. To the extent that its activity has at times overloaded the twitch chat system (no small feat considering the huge influxes of inputs Twitch is used to dealing with), TPP has now been running for over seven days with concurrent viewers / players often numbering in the hundreds of thousands. On paper it sounds like a fantastic idea. It is one of the largest massively multiplayer events to have ever taken place, where hundreds of thousands of players actions converge upon the crucible of a series of actions. A truly connective and democratic mode of play that fairly synthesises the inputs of players into one final end product. At times there is an enormous sense of accomplishment here as the audience / players collectively revel in any progression that is made in-game safe in the knowledge that they, in some small sense, contributed towards the outcome. Progress is however, slow.

For all the well made arguments supporting the potential of large scale collective action that I often draw upon here on this very blog, the amalgamation of playful inputs assembled in TPP is nothing short of a mess. At present, the game stands at 8 days and 10 hours of playtime with progress amounting to roughly 3 or so hours of regular play from a single person. In contrast to a collectively intelligent (Levy, 1997) or wise crowd (Surowiecki, 2005) mode of play that TPP represents, it has become emblematic of a chaotic collection of uncoordinated noise. The typical viewing experience of watching ‘Twitch plays Pokemon’ is almost an ironic self-parody of the sharp and focused speed runs built around the ‘twitch’ response that the popular streaming platform borrows its name from. Red, the character everyone collectively controls, is often seen walking around in circles, browsing through useless items, backtracking on himself and effectively carrying out ill fated actions. If there is any sensible and coordinated effort on the part of players to progress through the game it is drowned out as the different inputs, troll commands and stream delay all assemble together to create an eternal struggle that does not look to reside any time soon.

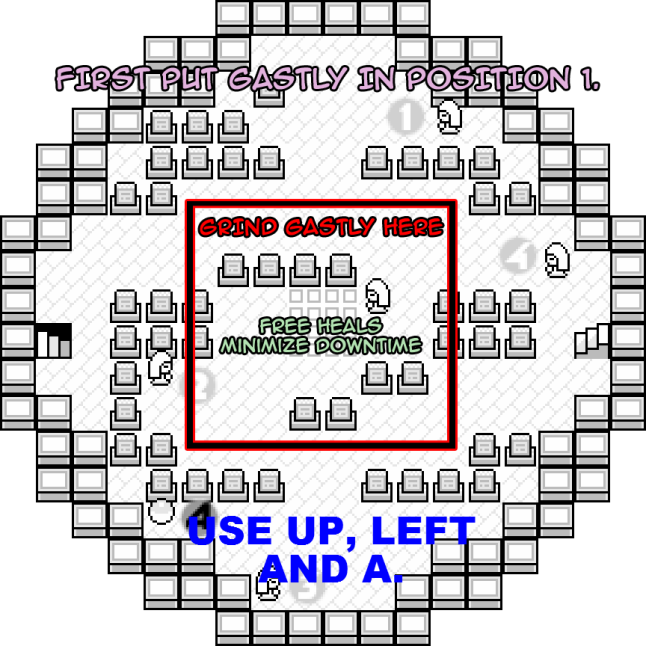

Watching TPP, one can’t help but be reminded of Jaron Lanier’s (2010) critique of the dehumanising quality of digital technologies and in particular, the polemic of collective actions that destroy any sense of cohesion or expression. It may be out of its original context but Lanier’s assertion that “we should instead seek to inspire the phenomenon of individual intelligence’ is a theme that instantly resonates when watching TPP play out. As much as TPP may crystallise many wider issues surrounding technological expression and freedom however; it has also grown into an extremely unique social experiment. Outside of the stream and the never ending inputs of the chat box a thriving culture has built up around the game as players attempt to bring order to this seemingly chaotic milieu. Similar to so many fan cultures that attempt to collectively solve seemingly impossible challenges (Jenkins, 2006: 25), the culture surrounding TPP is paradoxically trying to achieve Lanier’s wish for more individual intelligence by overcoming its very own existence as a connective one. In order for progression to be made here some semblance of order is required and in places of discussion such as the thriving subreddit for TPP, that task has begun to be methodically broken down.

The original developer of this experiment, an Australian programmer who wishes to remain anonymous, has also aided this goal by adding the commands of ‘democracy’ and ‘anarchy’ to help bring further order and control to the game. Anarchy mode is the ‘classic’ mode, where everyone’s inputs are applied immediately. Democracy mode chooses the most popular input provided during a 20 second voting period. Although any consensus on the effectiveness of these commands is still not clear, the distinction of ‘democracy’ and ‘anarchy’ has lead to a division within the community as some wish to democratically progress the game and some wish to see the anarchistic style of play manifest. Identities have begun to form around this distinction and players have begun making posters and supporting cases for various commands or ideological positions on how Red should progress. A parody of a religion has also arisen as players continue to make memes surrounding the commonplace action of Red to attempt to use the Helix fossil in the most inappropriate of places. Reflecting on the winter Olympics that are currently taking place, some posters have remarked that the experience of watching TPP is similar in that one can turn on the stream briefly to catch up with Reds story and due to the ease of participation, it is a story that so many people are now invested in. For the past week, TPP has lifted Pokemon Red to one of the most popular streams on twitchtv and if it remains beyond the control of Nintento who have a history of actively interferring in fan activity, then it’s uncertain how this new mode of play could continue to develop.

What is certain however, is that as painfully slow as progress may be, it is being made here. In Steinkuehler’s account of the playful practices of the early Lineage 2 player base the term ‘interactively stabilised’ is coined to describe the way that rule systems are slowly brought into a state of functional balance by players and sometimes developers who are invested in the game. TPP is a unique example of collective play that finds itself going through that process of interactive stabilisation. Exactly how much order or potential this mode of play carries is unclear but for now at least; its popularity is staggering and as with so many seemingly insurmountable tasks, the devotion shown towards the play through of this unique Pokemon Red game is demonstrating both the enormous dangers and potential of collective online actions.

Bibliography

Jenkins, H. (2008) Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, London: New York University Press.

Lanier, J. (2010) You are Not a Gadget: a Manifesto, New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Levy, P. (1997) Cyberculture, trans by Bonnono, R. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Steinkuehler, C. (2006) ‘The Mangle of Play’, Games and Culture, Volume 1: 3, pp 119 – 213, July 2006.

Surowiecki, J. (2005) The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many are Smart than the Few, London: Abacus.