A couple of weeks ago I took part in an interesting discussion on the subject of agency in games and in this post I want to weigh up the two positions we argued over and indeed, that are often argued about by players, developers and scholars alike. Who is playing who? With a specific look at the Eternal War gameplay experience, this article seeks to confront this issue.

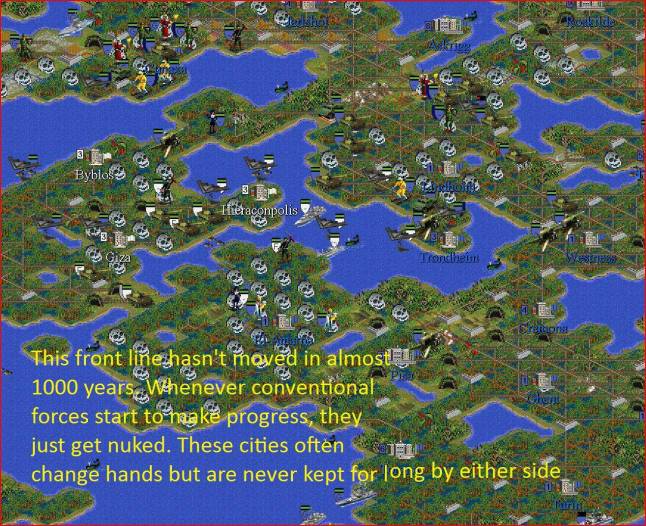

Sid Meier once stated that gameplay is ‘a series of interesting choices’ and in many ways it sums up the position that human agency plays the key role in the construction of play experience. Thinking about Sid Meier’s games it is easy to see his point. The story of ‘the Eternal War’ gameplay experience that came to Internet prominence last year is a prime example that in many ways represents this position. The Eternal War was a game of Civilisation 2 played by an individual on and off for over 10 years and during this epic encounter the setting of the game changed beyond usual recognition. As the player of this game, Lycerius, told this story to the reddit community and made the save file open to download the reaction soon spread across the Internet and wider media. Many heralded this experience and its accompanying Orwellian story as a breath of fresh air on an old genre. Many fans created fictions, artwork and there is still ongoing talk of a novelisation of the premise. Unlike a ‘total conversion’ mod or newly imagined gaming premise where this type of originality is more commonplace, the example of Lycerius and his now famous gameplay experience shows perfectly how the player can direct the experience of a game in ways the developer never imagined.

In many ways the Eternal War is an archetypal example of how gameplay is a legitimate form of interactive agency with a game and this is a position many academics have taken when understanding games. In Aarseth’s (1997: 1) description of ‘ergodic literature’ or the ‘cybertext’ he describes the difference between reading a book and playing a game as precisely a matter of human agency.

“The performance of their reader takes place all in his head, while the user of cybertext also performs in an extranoematic sense. During the cybertextual process, the user will have effectuated a semiotic sequence, and this selective movement is a work of physical construction that the various concepts of “reading” do not account for.”

The Eternal War can be viewed as a direct consequence of this ‘selective movement’ and indeed, given the playtime that was required to achieve this unique scenario (hundreds if not thousands of hours) ‘enduring movement’ may also be an appropriate description here. Referring back to Aarseth’s comparison to a linear book, it is easy note these differences as a unique consequence of ludic interaction. Put bluntly, the mechanics of games allow for reimagining’s of the presented premise in ways linear books cannot achieve beyond the inner thoughts of a person (as Obsidion writer Chris Avellone recently expressed). The Eternal War is often described in Orwellian terms referring to the scenario’s post (post, post, post, post…) -apocalyptic power struggle between two radically different super powers. In a BBC Radio four piece about the play experience one clearly inexperienced gaming radio host commented on this set of events as clearly inspired from Orwell. However that is not the case. Civilisation 2 is simply an open ended game designed primarily for a utopian ending (the typical game see’s one nation rise above the rest to eventually explore a new inhabitable planet), the Orwellian landscape the game took was the direct consequence of the players actions and the games mechanics pushed to an extreme.

The role of the games mechanics is easy to understate in this example however despite the play experience causing a complete reimagining of the setting, it is still Civilisation 2. You can still build the same units, attack enemies in the way the game allows and end your turn at the same time. This is the relationship Aarseth imagined when he coined the term cybertext and many scholars have since adopted similar stances with relevance to games. Giddings and Kennedy (2008) take a stance much more in favour of the role of the machine, or game mechanics when reading this relationship. Although G+K also employ cybernetics to describe the intertwined push / pull relationship players have with games, they state that even at the level of a master, ‘the player is mastered by the machine’. The Eternal War is an interesting example from this perspective because a players actions created the unique scenario that captured the imagination of thousands, not the developer. However the developer still made that player encounter possible. It may not have been an intended consequence of the original game however in a similar vein to the existence of many mods or examples of ‘counter play’, this prolonged play story is still inspired from the original premise. It is a cybernetic scenario manifest. A complete reimagining of the original premise built upon the unique play of a person afforded by the means of a machine. In essence this is what all games are and although the push or pull or some games mechanics or types of play might exert themselves in different ways, there is always that tandem.

The Eternal War may stand out as a pronounced example of player agency creating something original out of nothing more than a games mechanics however the mechanics are still the substance of that whole process. The moment the player or the machine becomes totally dominant in the dynamics of a game is the moment a game ceases to be a game. Hence games are always in essence, a cybernetic experience never wholly in the domain of a machine or person.

Aarseth, J, E. (1997) Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature, London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Giddings, S. and Kennedy, H. (2008) ‘Little Jesuses and *@#?-off Robots: On Cybernetics, Aesthetics and Not Being Very Good at Lego Star Wars’, in Swalwell, M. and Wilson J. (2008) The Pleasures of Computer Gaming: Essays on Cultural History, Theory and Aesthetics, McFarland: Jefferson NC, pp 13 – 32.